Why Are We Making Our Children the Victims of Bad Religious Art?

https://onepeterfive.com/children-victims-bad-religious-art/

Why Are We Making Our Children the Victims of Bad Religious Art?

Walking out of church this week, I noticed a pile of free children’s pamphlets/Mass supplements at the door. I was so annoyed by this smushy and blobby cover that I picked it up to see if the inside was just as annoying. It was. And it got worse. (This item will be listed as Nameless from here on.)

Why can’t we have pictures of people with proper faces? The face is the thing children most focus on from birth. The pages of Nameless were full of cartoons and scribbly-style drawings. The message this sends is that everything in this disposable booklet is of no more consequence than Bugs Bunny or Toy Story.

Two pages later, and I was ready to blow a gasket. This was the picture that bothered me so much:

Take a closer look, and you will see that the scruffy dude in the baggy pants has his belly button showing. We are treated here to a complete array of clothing styles: dress and hat, tank top, shorts, and belly shirt! This picture makes them all equal, all equally acceptable for going to Sunday Mass. The message is this: it doesn’t matter what you wear to Mass. It doesn’t matter how you look. All that matters is that you show up. Is there no more to it than that?

Are we really going to give this garbage to our children every Sunday, year in and year out, as their aesthetic nourishment for Mass? I began to wonder how many parishes in the United States subscribe to Nameless. Probably thousands. That means potentially tens of thousands of children looking at the visual equivalent of Twinkies and Pepsi.

What’s more, this is not the only children’s resource like this. I have looked at many children’s Bibles and seen many regrettable Catholic picture books. The majority of them now fall into the trap of aping Pixar, as if the norm for artistic expression is animated big-screen cartoon characters [i]. Thus, I have no intention of singling out Nameless for particular abuse. However, Nameless is especially noteworthy because the company’s products are in so many parishes and because their adult booklet is aesthetically a cut above the usual Catholic offerings.

When my children were very young, we lived in Europe. I came to be fond of the picture books of a popular French children’s illustrator named Maïte Roche. The books were simple, sweet, calm, and earnest. Perhaps not perfect, but far better than most of what I had seen in the USA. At least Jesus came across as a real person, inviting and attractive, instead of being depicted as a cartoon character with no special qualities. Here is a sample from one of Roche’s books:

When my children were a little older, and we were back in the U.S., I found other resources I thought were even better – for example, Moira Farrell’s My First Eucharist coloring book, part of a Montessori-based preparation for First Communion. Using simple line drawings, the artist manages to make the tabernacle and Church obviously some place special, set apart, and even transcendent:

David Clayton’s coloring book God’s Covenant With You has similar qualities.

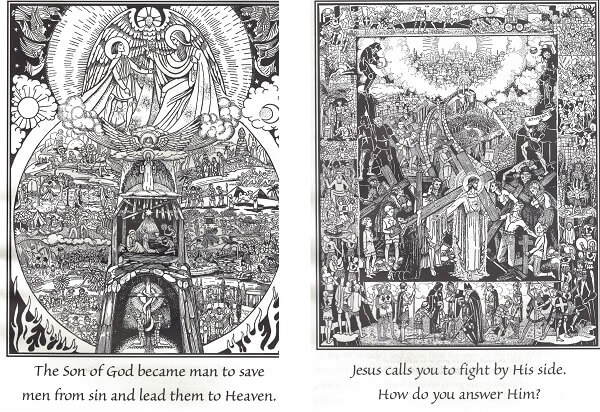

Then I discovered My Path to Heaven by Geoffry Bliss, S.J., with illustrations by Caryll Houselander. Houselander knew that the combination of a strong overall design with intricate busyness would fascinate a child (yes, a slightly older child), drawing him in and connecting his imagination to the depth of meaning that goes with the text:

When we come to the realm of the liturgy proper, there are several worthy children’s missals available for the usus antiquior. Since the traditional liturgy itself is so full of dignity, order, and beauty, it generally summons forth the same qualities in the work of those who attempt to illustrate it. One example:

The priest here is dignified and reverent. All of the pictures in the missal are focused on the Eucharistic action and its intense sacredness [ii]. In contrast, here is the one and only Eucharistic picture in that issue of Nameless:

Who said a picture is worth a thousand words? This picture is worth a thousand tears.

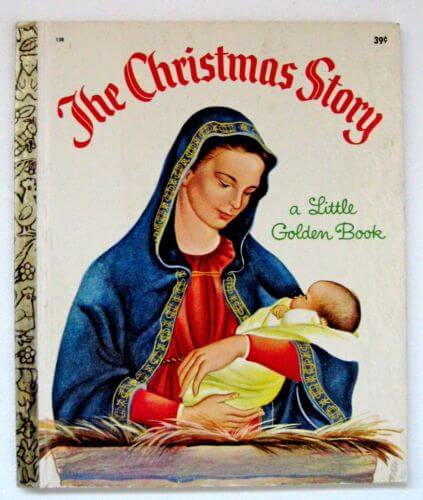

As a mother and (when time permits) a painter, I know something about children’s psychology and about the messages we send through art – through the beauty of it, or the lack thereof. I also know well a little girl whose first evangelization was through religious art. Raised in a pseudo-Christian cult, my first real catechesis, at the age of four, was with the Little Golden Book version of The Christmas Story by Eloise Wilkin. I spent hours poring over the pictures of Mary in that book.

I distinctly remember looking at these and saying to myself over and over, I want to be like Mary. Why? No one ever talked to me about Mary. No one told me to be like her. Yet there was nothing else in my entire world like those pictures. I know now that it was because they were modeled on Catholic illumination and fine art. Look at the gold border around Mary’s cloak (which doesn’t show up well in a computer graphic) [iii]. To a child who knew nothing of true Christianity, the art successfully communicated a message to me, without the need of a single word: Mary is special, Mary is noble, Mary is utterly worthy of being imitated and loved.

Looking back, it’s clear to me that the Holy Spirit was at work through that imperfect but sincerely reverent art. How, or what, will the Holy Spirit communicate through the cartoon and blob-style saints and Christs in things like Nameless?

To the objection that children are “not ready” for real art, that they would be overwhelmed by it or bored, the response is simple: children are naturally ordered to becoming adults, and if they are not artificially held back by a diet of childish fare, they will desire to work their way up into the world of adults. There is a reason why we use the phrase “bringing them up.” The child wants to understand what adults are talking about, wants to speak their language, to be treated as an equal. Hence, what parents value is what their children will eventually value. This much is common parenting experience. If we love beautiful things, if we take pains with how we dress, how we speak, the kind of music we listen to, the art we put in our homes and enjoy looking at, and we share regularly with our children why such things matter to us, they will absorb the influences and be on the lookout for the same in their own lives. They will grow into the beautiful, for God created the human soul to rejoice in it and rest in it.

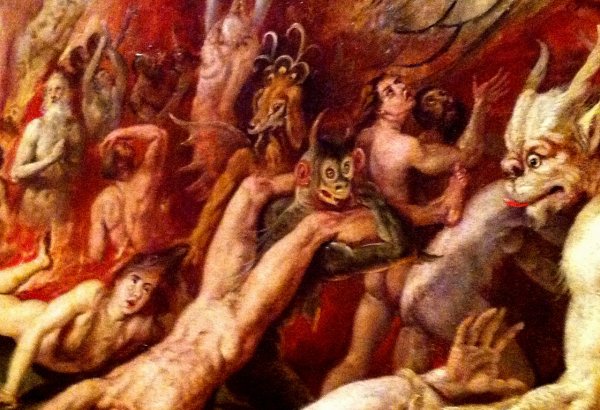

In any case, there is never any excuse for cheapness, pandering to the lowest common denominator, or chasing after the latest fashions. Putting bad art into the eyes, the imagination, and the memory of children deforms them and may place obstacles between them and an encounter with the God, Who is sovereign Beauty. It may even erect subtle psychological barriers to living the fullness of liturgical and sacramental Christianity, for it does not take much intelligence to see that if the Faith is true, it surely cannot express itself in trite, superficial ways. The lamentable fact that the Faith is so often expressed in trite, superficial ways transmits the underlying message that the Faith is not true.

St. John Chrysostom, speaking about icons, says the honor given to the image passes to the original. By extension, if we make images that dishonor Our Lord or Our Lady, isn’t that dishonor also passing to the original?

Look at how Blessed Angelico, whom John Paul II declared the patron of artists, depicts the child Christ:

One might compare the famous Nativity scene painted by Giotto:

Our Lord Jesus Christ is fairer than the sons of men. As God, He is Beauty itself and the source of all created beauty. Of course, this cannot be depicted by poor mortals like us, but there are centuries of fine art in our Catholic tradition that manage to convey something of the mystery of divine beauty. Every children’s book intended for religious use should be drawing heavily upon this immense heritage of beauty, this inexhaustible fund of iconography that is our birthright as Catholics [iv].

At very least, we should have enough respect not to turn God Incarnate into a cartoon character.

NOTES

[i] To me, this is eerily reminiscent of the society in Farenheit 451, where Jesus is only a character in TV shows.

[ii] Those looking for a basic Tridentine missal illustrated throughout with classic art should consider A Missal for Young Catholics.

[iii] Sadly, this is no longer the cover used with recent editions of Wilkin’s book, probably because it is too Catholic.

[iv] There are such books available. Here are two that use Giotto and Fra Angelico: The Saving Name of the Son of God by Jeanne Sharpe and The Nativity by Geraldine Elschner.

Comments

Post a Comment